Being a subtitler is a strange part of the filmmaking process and subtitlers are, without doubt, the unsung heroes of it. Film production takes a huge volume of man hours and vast resources. It requires the cooperation and special expertise of a slew of people from a variety of fields.

You need actors and researchers, set and costume designers, location scouts and cinematographers, in order to realize a vision from the screenplay to the screen.

During that process, the producers and director carefully oversee every detail. Any failure in any department along the way could compromise the whole artistic vision of the filmmakers, and the film could collapse.

It’s a fundamentally collaborative process requiring an ongoing dialogue and support system from within to create a product consistent with the artistic vision.

When the film is finished, though, something inexplicable happens. The final cut that everyone worked so hard for is haphazardly handed off to a third party!

This party (often made up of subtitlers) has the power to enhance or destroy the audience’s experience of the film. If the subtitlers do their jobs well, they bring the filmmakers’ vision to whole nations of new viewers. If they sacrifice quality for time, the film could become a laughingstock.

But instead of the support and collaboration that every other member of the crew enjoys, subtitlers work alone and are often instructed to crunch their work in a matter of days. And despite the high stakes and skill involved in their part of the filmmaking process, they usually don’t have any contact whatsoever with the film’s director.

The solitary, unsung heroes of international cinema are the subtitlers. An afterthought in the filmmaking pipeline, but the responsible party in delivering the filmmaker’s vision across linguistic borders.

Related Post: Why Subtitling is Better Than Dubbing: Every Single Time

Getting to Know Your Subtitlers

In the short documentary The Invisible Subtitler, Brazilian Portuguese subtitler, Amanda Jorgensen, points out that many films will have a glossary of terms for the actors, if for example they’re shooting a war movie.

While the filmmakers could easily pass this glossary on to assist the subtitlers, ensuring that the accuracy of the script and nuance of the performances are preserved, they usually don’t take such steps. The subtitlers are left to their own devices.

And unlike literary translators, who are acknowledged on the cover or the front page of the novel they translate, subtitlers are almost never credited. At most, you might see the name of the company that contracted them.

What Exactly Do Subtitlers Do?

Subtitlers are first and foremost translators, and must understand the source and target languages with the sophistication of a translator. Originally, the subtitlers handled the whole subtitling process, including the technical aspects of digitally applying the text to each shot of the film.

Subtitlers make sure that the titles line up with cuts in the film. If subtitles linger during a cut, they can disrupt the brain’s ability to process them smoothly. This process of timing is called ‘spotting.’

The text also must correspond to the audio. It normally appears just as the brain is becoming aware that the actor is speaking, the moment the viewer unconsciously begins to wonder what the actor is saying. A perfectly timed subtitle appears as a response to that silent question.

The text will linger a moment after the actor finishes speaking.

The distribution of words is also important. Conjunctions like because or and should appear on the second line, or on the next subtitle. Text should usually be broken up like this:

If you become a bird

and fly away from me

Reads much more smoothly than this:

If you become a bird and

fly away from me

The latter implies a stutter after the word and. It’s not a natural place for a pause. Details like these go undetected to the audience, and they should. But quality subtitlers always have them in mind.

There is a myriad of little decisions that subtitlers make. If the voice is offscreen (voice over, or VO) they usually italicize the subtitles. But what if the VO is reading text that appears onscreen, like a shot of a letter? Subtitling the VO doubles the text, but most subtitlers would agree it’s important to have them anyway.

Related Post: These Hilarious Subtitling Errors Are Too Good to Be Missed!

Source Language or Target Language Fidelity

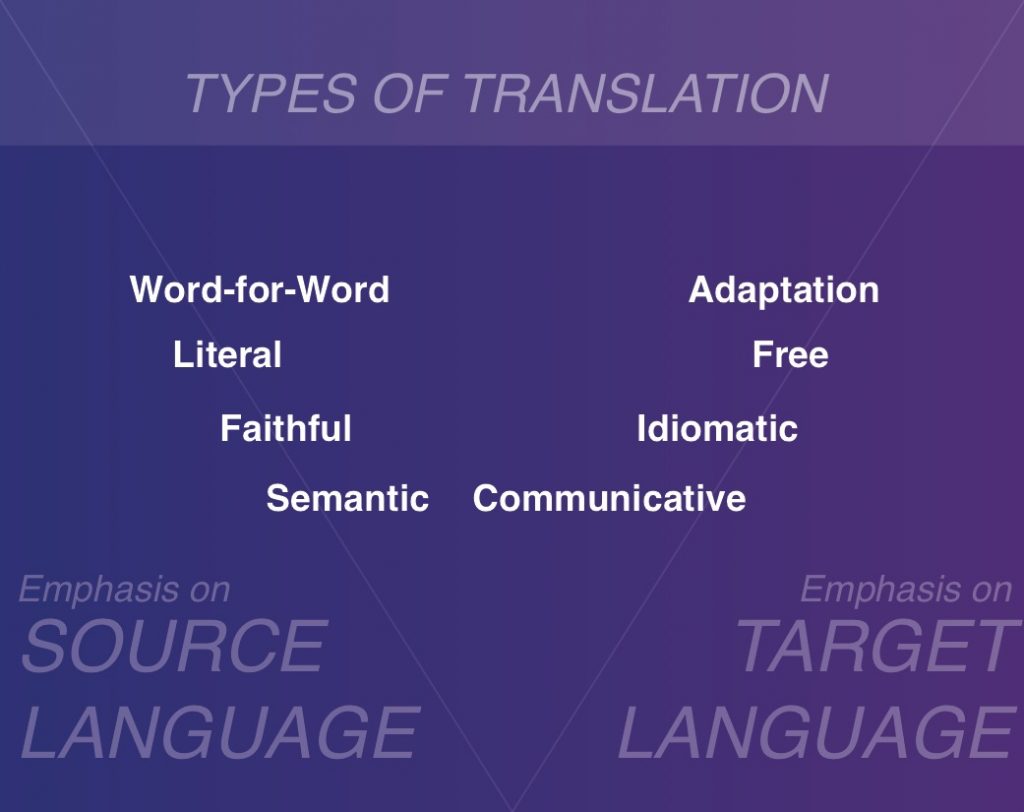

In A Textbook of Translation, Professor of Translation, Peter Newmark, explores the translator’s fidelity to either the source language (SL) or the target language (TL). The variations create many different styles of translation.

For example, translating a sentence word-for-word might be technically true to the source material, but could lose a lot of cultural context. A semantic translation, on the other hand, might depart from the literal meaning of the source in order to preserve the rhythm and flow of the text.

Additional types of translation are literal, faithful, communicative, idiomatic, and free translations, as well as transcreation and adaptation, which is liberal enough that it is hardly considered translation anymore.

It is up to the discretion of the subtitlers which type of translation is best. Some of these types are outlined as follows, with Newmark’s definitions:

Newmark’s Types of Translation |

|

| Word-for-Word Translation | TL words immediately below SL; SL word order preserved; context ignored; cultural words translated literally; usually used for language study |

| Literal Translation | SL grammar is converted to TL equivalents; lexical words still translated singly and out of context |

| Faithful Translation | Aims at reproducing contextual meaning of SL within the constraints of TL grammar; transfers cultural words; deviates from SL norms; focuses on intent of SL writer |

| Semantic Translation | Takes into account aesthetic value of SL; makes compromises to preserve assonance, word-play or repetition; allows more creativity from the translator |

| Communicative Translation | Attempts to render exact contextual meaning of the SL so content and language are both comprehensible to TL readers |

| Idiomatic Translation | Reproduces the ‘message’ of the original; distorts nuance by using colloquialisms in the TL where there are none in the SL |

| Free Translation | Reproduces the matter without the manner; content without the form; usually more like a long form paraphrase than a translation |

| Adaptation | The freest form; themes, characters, and plot are preserved; SL culture converted into TL culture; usually used for poetry or comic plays; not really translation at all |

These types exist on a spectrum, ranging from emphasis on the SL to emphasis on the TL. Newmark arranges them in the following V shape:

Do subtitlers put more emphasis on the source language or the target language? It’s a tricky balancing act, of course.

Most subtitlers use semantic translation for the film’s title, and semantic or communicative translation for the subtitles, according to a study by the School of Foreign Languages at Jilin Agricultural University.

Related Post: Transcreation vs Translation: What’s The Difference?

Treating Culturally Sensitive Material

There are cultural sensitivity issues to take into account, as well. A Chinese subtitler often goes to great lengths to render the dialogue inoffensive to the Chinese government or the cultural sensibilities of the audience.

Studios changed the subtitles of the James Bond picture Skyfall, for instance, to remove a reference to a prostitution ring in Macau. And there’s a whole PhD thesis written on the often hilarious ways in which Chinese subtitlers have handled the bawdy antics of Sex and the City.

Some countries with more conservative cultures may object to overtly sexual or profane content that countries like the USA consider normal. Another study by the National University of Malaysia reviewed 112 instances of sexual or profane language in four English language films.

It found that in instances where language was not considered appropriate for Malay audiences, a subtitler might use translation styles like modulation or equivalence translation.

Modulation is when the point of view of the SL is change in the TL; equivalence is when the the TL describes the SL situation by different stylistic and structural forms.

Subtitlers treated the 112 instances the study surveyed with the following translation techniques as they translated into Malay:

| Treatment of Profanity in Malay Subtitling | |

| Literal Translation | 32.6% |

| Modulation | 3.3% |

| Equivalence | 46.7% |

| Adaptation | 7.6% |

Almost a third of the time the subtitler left the objectionable material intact. But nearly half the time they treated it with equivalence translation, which has much more plasticity and allows the subtitler to tiptoe around the sensitive words or phrases.

Saluting the Unsung Heroes of Cinema

Cultural sensitivity, translation style, timing, rhythm and cuts, and working in solitude without supporting information from the director or producers–holding all these things in the balance is no small task. By now you’re doubtless beginning to see the delicacy and skill that good subtitlers exact.

Since the early 2000s, though, many companies started breaking up the workflow to reduce costs. They outsourced many of the technical aspects of the subtitling process to non-linguist computer technicians. This meant that subtitlers had less control over their projects, and companies had an excuse to pay them less. It’s left subtitlers more in the dark than ever before, even as demand for subtitling increases.

A lot of time, money, and man hours go into producing a film and getting it exactly the way the the filmmakers want audience to view it. A good subtitler handles their duties with elegance and high standards of quality, knowing that they will never receive due thanks or credit.

So let’s have at least this moment to say thank you to the unsung heroes of the international film industry! Here’s to you, subtitlers!

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.