We often take it for granted that we all see the world the same way. But did you know that some languages don’t differentiate between green and blue? The blue-green distinction is a focal point for the study of the development of language. This color distinction tends to arise at a certain stage in a language’s evolution.

Many languages, such as Korean, Tibetan, Vietnamese and Yoruba, have the same word for blue and green but use the sky and the leaves as reference points. A speaker might say “blue like the sky” (as in the Vietnamese xanh da trời) or “blue like the leaves” (xanh lá cây) to make a blue-green distinction.

The Khmer word for blue, ពណ៌ខៀវ (bpoa kiaw), includes blues and greens. Words for green, like ព័ណ៌ស្លឹកចេកស្រស់ (bpao sloek chek srasa, literally “color of fresh banana leaves”), are more specific and do not include blue.

Choctaw historically had no blue-green distinction, but they do distinguish between dark blue-green (okchʋko) and light blue-green (okchʋmali). There’s another word entirely for parrot-green (kili̱koba, after the kili̱kki bird). However, modern usage has introduced a blue-green distinction, and now the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma applies okchʋko to dark and light blue and okchʋmali to dark and light green.

The Tupian language also gained a blue-green distinction, only after colonial invaders brought it from Europe.

How Language Describes Visible Light

As languages evolve, their ability to describe the world gains complexity. According to the Berlin-Kay theory of basic color terms, the first description of color to emerge in a young language is the differentiation between light and dark.

From there, the language will gain words for long wave light (“red”), middle wave light (“green”), and short wave light (“indigo”). Words for pink, purple, orange and gray are the last to arise, and will do so only after all other basic colors have been named.

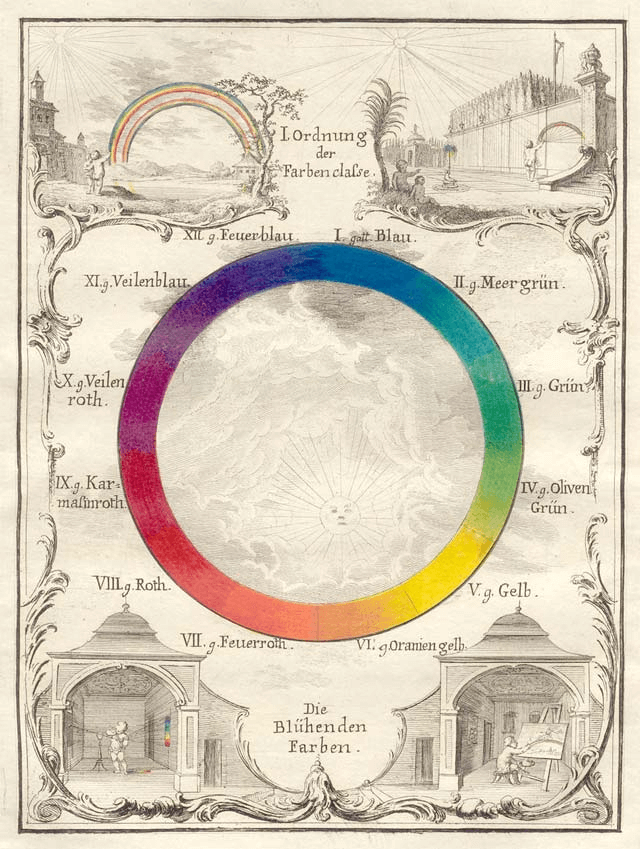

This chart shows the color boundaries used by most European languages:

Image: Wikipedia

Those boundaries, however, are more or less arbitrary, because there is really no border on a rainbow between a 475 nanometer light wave (the wavelength we recognize as “blue”) and 510 nanometer one (“green”).

Wavelengths, incidentally, are the reason a rainbows bends. The innermost color, violet, has a short wavelength, while the outer red has a long one. But each color fades into the next, and whether we make a blue-green distinction, or any other distinction for that matter, is largely up to our language programming.

Six Kinds of Blue-Green Distinctions

Paul Kay, for whom the Berlin-Kay theory is named, studied the color terminology of 110 languages around the globe. According to his research with Luisa Maffi at the University of California, Berkeley, there are six ways languages make blue-green distinctions:

- Green and blue each get their own word, like in English

- The blue-green spectrum gets one word (“grue”)

- One word defines black/green/blue

- There’s a word for blue/black and another word for green

- All greens, from yellow-green and blue-green, get the same word

- There’s a word for yellow/green and another word for blue.

The most common of these blue-green distinctions is the second, a “grue” term that describes blues and greens together. This amazing map shows the distribution of these six types of blue-green distinctions around the world.

Differing Theories of Primary Colors

Traditionally in western kindergartens there are 3 primary colors: red, yellow and blue. These mix to create 3 secondary colors: orange, green, and purple. Between the primary and secondary are tertiary colors like reddish-purple or yellow-green.

Arrange all these colors consecutively, and you produce a color wheel, such as this one by Austrian naturalist Ignaz Schiffermüller in 1772:

Image: Wikipedia

We also have three kinds of color sensors, or cones, in our eyes. Instead of red, yellow and blue, however, they detect red, green and blue. The trichromatic theory of human color perception is based on the idea that because of these cones, every visible color comes from combinations of red, green and blue, similar to the way color works on a computer screen.

An alternate view called the Opponent-Process theory, however, suggests that there are 6 primary colors and not 3, arranged as pairs of opposites: yellow-blue, red-green, and black-white. You can think of these polarities as an x, y, and z axis.

Arranged this way, they produce a color sphere that’s light at the top and dark at the bottom, with yellow, red, blue and green around the equator. If you sliced this sphere in half like an orange, the cross section would be a color wheel. This is a bit more like the CMYK colors used in printing.

There’s no one correct way to explain color perception, or at least not yet. And that makes for a lot of variations in how colors are described through language. And because color is so complex, it’s impossible to nail down any kind of objective labeling for the visual sensations we have. So a blue-green distinction might just be a product of cultural programming.

Language Impacts How We See

The American Psychological Association describes a study by Debi Roberson of the University of Essex, who compared English children learning their colors with children of the Himba tribe of northern Namibia, who were learning colors in their own language. The study revealed that color is much more culturally relative than we thought.

In short, the range of stimuli that for Himba speakers comes to be categorized as “serandu” would be categorized in English as red, orange or pink. As another example, Himba children come to use one word, “zoozu,” to embrace a variety of dark colors that English speakers would call dark blue, dark green, dark brown, dark purple, dark red or black.

English has eleven words for basic colors (red, blue, green, yellow, orange, black, purple, white, brown, pink, and gray). Himba has only 5, but they cover broader spectrums of hues.

The results of their Roberson’s testing suggested there’s no innate origin for the eleven English color categories. Nor did any of the children learn colors in any predictable order, debunking the universalist idea that we understand primary colors first. So the definitions we give colors in English may be useful, but they are invented and arbitrary.

And it gets even weirder than that. The Himba’s five basic colors are:

- Serandu: red, orange and pink

- Zoozu: black and dark shades of red, blue, green and purple

- Vapa: white and some yellow

- Borou: greens and blues (lacking the blue-green distinction)

- Dumbu: other greens, red and brown

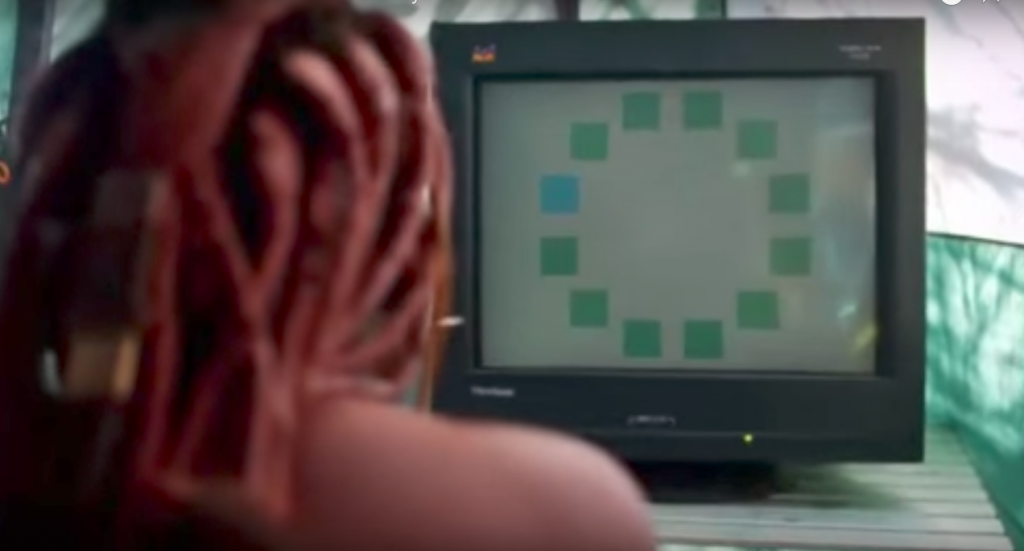

The way Himba language organizes colors differently, compared to western languages, actually impacts the way they see. Take a look at the image below, and see how fast you can pick out the square that’s a different shade of green:

Image: https://static01.nyt.com/images/2012/09/04/magazine/046thfl-green-color-ring/046thfl-green-color-ring-blog480.jpg

In the BBC documentary Horizon, Himba people quickly and easily pick out the northwest square as the odd one. That’s because the two kinds of green here are labelled with two different Himba words, so they see these colors as unrelated (if you don’t believe your eyes, check out the color analysis by Mark Frauenfelder at Boing Boing).

On the other hand, the Himba had a difficult time picking out a cyan square, which a westerner can do quickly and easily. That’s because the Himba use the same word for both of these hues.

Image: YouTube

This suggests that language informs our experience of color to an astonishing degree, and we are very literally seeing the world differently from our neighbors.

Without the Blue-Green Distinction, What are Blue and Green?

The blue-green distinction and the five Himba colors show that color and language are inextricably linked. Language helps us organize the sensations that color produces, but it also transforms our experience of them.

So the next time you’re overlooking a pastoral landscape, watching a brilliant sunset or observing a painting at a museum, see if you can switch of your color labeling language. It may give you an experience altogether different than the one your linguistic programming imposes upon the moment. If color is relative to your language, what is color?

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.