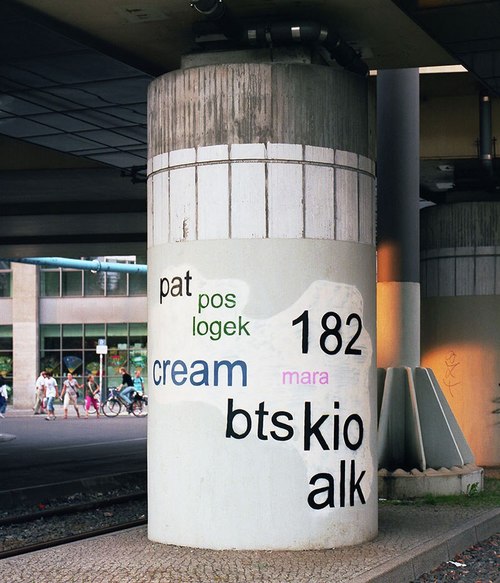

If you’ve visited Strasbourg, France, you may have encountered a strange sight: walls of public graffiti painted over and replaced with pristine, sans serif text in a bid at translating graffiti.

In a project called Tag Clouds, artist Mathieu Tremblin took it upon himself to update urban spray painted scrawls into a more legible typeface. His recreations replicate the original taggers’ content, scale, layering and even the colors, updating them to an HTML style font.

Images by Mathieu Tremblin

The artwork is more than just a playful prank. It sheds light on graffiti as one of the world’s least understood–and least translated–languages. By clarifying and translating graffiti, instead of covering it up, he brings the sometimes obscure writing into the light of day.

How Graffiti Became a Modern Language

Modern graffiti is a language largely developed in urban centers like New York City, starting in the 1970s. During that time, funding for arts education in public schools was down. Kids started tagging walls and subway cars as a form of self expression.

“Media called it graffiti, but we called it writing. We were just writing our names in the beginning,” says Sacha Jenkins, cultural historian and creative director of Mass Appeal magazine. “It’s a language people aren’t familiar with.”

Jenkins was there during the graffiti boom in the last decades of New York’s 20th century. More recently, he co-curated a gallery exhibit there called Write of Passage. It chronicled the golden age of wall and subway graffiti in 1970s New York.

Write of Passage sought to help show people how to understand graffiti and its evolution, translating graffiti and making it accessible to all.

Many associate graffiti and tagging with urban gangs, but “it’s not a bunch of violent thugs and gang members,” argues Jenkins. “There’s a good deal of culture and respect and rules and ideas and ingenuity that went into developing this language.”

Taken as a language unto itself, graffiti presents some unique and interesting quirks. There’s little in the way of centralized stylization or formal regularity.

This makes it difficult to codify. In short, every writer has a different visual and linguistic style, and that’s part of the language, making translating graffiti particularly hard. Any given tag shows the hand of its owner. In that, it shares something with calligraphy as much as language.

Images by Mathieu Tremblin

The Difference Between Street Art and Graffiti

Over the years, graffiti and street art have diverged as different forms. Street art, which is based in visual imagery and is often representative, has developed into contemporary forms of muraling.

The gentry appropriated street art murals, and now corporate entities commonly commission them to beautify or market to gentrifying urban neighborhoods.

But that’s not the same thing as graffiti, which is a form of writing. While it does have a certain aesthetic, its goal is not beautification. In fact, many non-writers associate graffiti with derelict buildings, where it often accumulates, and therefore urban decay.

As writing, graffiti is a form of communication. When a writer leaves their mark on a train or the side of a building, they might simply be saying “I’ve been here.”

On another day, in another month, they may find themselves sitting on the same subway car again, and see their tag or their friends’ tag. It tells them they’ve been here before. Taken as a whole, tagging is like creating a real world Google map of all the places you’ve been.

Tagging in Digital and Real Space

In that way, a graffiti tag is very much like a digital tag. You’ll notice that this post is tagged with some of the topics at the core of its subject matter. We tag our posts to make some kind of meaningful grouping of identifiers. By looking at tag clouds, patterns and maps emerge. A tag cloud of this post reveals the most frequently occurring keywords:

Digital tag clouds, Tremblin says, are similar to graffiti tags.

“Tag Clouds principle is to replace the all-over of graffiti calligraphy by readable translations like the clouds of keywords which can be found on the Internet,” Tremblin told Memefest. “It shows the analogy between physical tag and virtual tag, both in the form (tagged walls compositions look the same as tag clouds), and in substance (like keywords which are markers of net surfing, graffiti are markers of urban drifting).”

Tremblin’s clever and thought-provoking public works, which he calls ‘urban interventions,’ rather than ‘street art’ or ‘graffiti,’ do more than tell a visual joke. They make connections where we might not have before.

“It’s the transformative power of art that matters. Discovering a work forces you to bend your mind and project yourself into the perception of someone else, in order to experience a new sensibility – in a way that it is otherness – with a horizon to achieve: to go beyond the definition art in order to return to life and to be intensely present to the world.”

By showing the world of graffiti from a new perspective, the artist is a translator. Through his work, effectively translating graffiti, the uninitiated can understand the language of graffiti, both literally because it’s crisp and legible, and figuratively because we must rethink what it means to write on walls.

Translating Graffiti

A few years ago, researchers at Indiana’s Purdue University were working with law enforcement to develop an app called Gang Graffiti Automatic Recognition and Interpretation, or GARI. The app was supposed to analyze, identify and store information about gang related tags. It was meant to help law enforcement track gang activity in the Indianapolis region by decoding or translating graffiti.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Science and Technology Directorate was one of the financial backers of GARI. They undertook this project as part of Purdue’s Visual Analytics for Command, Control and Interoperability Environments Center of Excellence (VACCINE).

“Gang graffiti basically tells a story,” says managing director of VACCINE Timothy F. Collins. “Investigators want to not only catch who put it there but also to understand its meaning. Sometimes they indicate when someone is about to get killed or whether a rival gang has moved in that could lead to an increase in crime. An officer might take a picture of graffiti and ask the system to show all the similar graffiti that has occurred within 2 miles of the location.”

The GARI app doesn’t seem to have materialized. But campus safety officers and law enforcement in urban centers around the U.S. are still trying to find ways of translating graffiti with the help of technology.

Images by Mathieu Tremblin

The Language of Graffiti and Culture

Perhaps the best way to understand this language, however, is not by translating graffiti or analyzing it from the outside, but by listening to those on the inside. People like Mathieu Tremblin and Sacha Jenkins are helping people understand graffiti not as a threat, but as an expression.

Any serious discussion around graffiti as a language and a reflection of culture needs to address the issue of vandalism. Because graffiti is illegal, it is by nature a countercultural act. While the legality is clear, the morality of graffiti is complex. It raises questions about the merits of private property in an environment of economic disenfranchisement, or for whom public spaces are really built.

Another issue is that with the normalization of a cultural device like graffiti comes the appropriation of it by more powerful cultures.

This already happens pretty commonly with street art, and we see it when higher fashion uses graffiti as a foundational aesthetic, for example. When a countercultural voice is translated into the mainstream, the meaning and content is compromised. Translating graffiti can mean diluting its voice.

In an interview with Citylab, Tremblin says, “Agreeing with or being against the piece as a graffiti writer is a complex thing to decide because I’m half paying tribute to and half normalizing the local graffiti scene. I just translate writers names at the same scale and they usually continue to play with the blank spaces, adding their signature between regular typography I painted with stencil. In fact, the project is giving focus to some walls that writers weren’t paying attention to anymore because they were filled with tags. Mostly though, it generates new graffiti challenges instead of killing the energy behind it.”

‘Making Intelligible a Whole Culture’

Wherever you stand, it’s easy to acknowledge graffiti as a language reflecting a culture of economic marginalization, and translating graffiti can help to make it more widely understood.

As languages and dialects blossom naturally and develop over time, so has graffiti become a nearly canonical language of urban life.

British artist Banksy, probably the world’s most famous street and graffiti artist, said that “it is one of the few tools you have if you have almost nothing.” As a voice for the voiceless, graffiti becomes an important translational inquiry.

According to author Anthony Burgess, “Translation is not a matter of words only: it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture.” By understanding graffiti as language, and by translating it with the same care we would use to translate Mandarin or Arabic, we begin to understand an urban culture. It’s a culture where the merging of art and language is a way of reclaiming the public space.

In its capacity as a language, graffiti is likely to be remembered one day as a cultural treasure. In the meantime, we can understand it today as a language. We can seek understand it, by translating graffiti, rather than just whitewashing it away.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.